| ||

The TeachersMr Brown

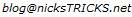

These completely random ladies on the street could married to the same man

Once I was walking with him through the crowded corridors between lessons. Finding his way blocked he good-naturedly grabbed a nearby pupil had pushed him backwards through the throng, using him as a battering ram to part the crowd as I followed in their wake. Perhaps due to such behaviour the pupils were clearly quite intimidated by him and didn’t dare step out of line in his lessons. His classes were more than simple language instruction, he clearly also saw it as his duty to educate the children in the ways of life, diverging from the task of teaching them English to lecture on why they should read the newspaper or the evils of corruption. One lesson was on the subject of “temptation”. He warned them against such vices as alcohol, drugs and prostitution that he suggested were tearing society apart. With no apparent hard drugs scene and one of the lowest rates of HIV infection in Africa I think this may have been something of an exaggeration. Interestingly prostitution could be split into the legal and illegal variety, legally registered prostitutes receiving the benefit of regular medical checkups, something that helped Senegal control the spread of Aids in the country before it got much of a foothold (in Wisdom of Whores, by HIV epidemiologist Elizabeth Pisani, Senegal's unsqueamish reaction to the epidemic is cited as the most effective in Africa). A lesson with a degree of sexual content was obviously going to get a group of teenagers chattering, but Mr Brown certainly played a bit to the crowd. Unlike other teachers he would quite often switch out of English into Wolof or French, usually to deliver a homily of some sort. At one point he switched to Wolof and reduced the class to stitches. I asked what he had said and he replied innocently that he’d explained they shouldn’t have sex if they wanted to avoid getting pregnant, then complained that the kids got very excited at what he had told them. I suspect hadn’t told me the whole story, and had perhaps suggested some sort of sexual contact that doesn’t run the risk of conception. On the way to one lesson he made reference to his own love life. A polygamist with two wives, he explained that there were so many women in Senegal that it was practically his duty to marry more than one or some would miss out. It was not the first time I had heard this argument in Senegal, and he insisted that there were demographic statistics to back this up, harassing another teacher nearby into confirming this. My own survey of the pupils in class did not fit this theory; the numbers were almost exactly equal. That, I was then told, was because often in rural areas the families would only send the sons to school, thus making the ratio of pupils unrepresentative. I have since looked up the World Bank statistics. There it is stated that women account for 50.8% of the Senegalese population, identical to the United States. Mr Fall

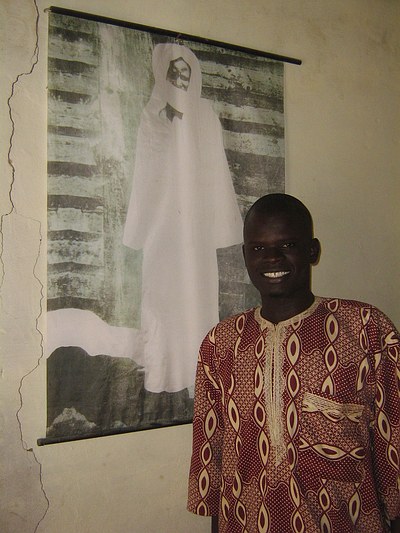

Mr Fall in his room next to a poster of Cheikh Amadou Bamba

At first sight Mr Fall cut a slightly awkward figure, walking as he did with a very heavy limp. As a result he had problems standing for the full duration of a lesson and his classes were arranged to be on the ground floor because he didn’t like climbing the stairs. He wanted to move on from teaching as some point as he found it physically demanding. Ideally he wanted to study further somewhere abroad, telling me that even in Senegal a foreign qualification was usually regarded more highly than a Senegalese one. But the world doesn’t necessarily offer great opportunities to an African English teacher, who doesn’t speak English brilliantly, and whose meagre earnings are already spread very thinly. However, he was a genuine man with a very generous nature and we become good friends. After lessons I would accompany him to the very humble room that he rented. He would unwrap bandages from his withered leg, pray to Mecca and use an off-cast computer from the school to play some audio files of Islamic verses. After eating we would prepare lessons and I would quiz him at length about Senegal. The most notable differences between our respective societies were in the role of the family. In Britain, probably more so than even its neighbours, school leavers are anxious to establish independence from their parents. The preponderance in of British volunteers in St Louis on gap years before leaving their hometown for university was testament to this. Mr Fall was actually breaking slightly from the Senegalese norm in that he wasn’t living with his family while unmarried. He visited his parents every weekend in a large town an hour or so away. He would much rather live with them but he was only able to find his first teaching job in St Louis. While I was at his room one day his half-brother called him from America, apparently he had been working there for ten years or so. Mr Fall was very scathing of him because he didn’t feel he was in touch with the family enough, and because he didn’t send money back. The brother had returned to Senegal only twice in the decade he had been away: once to marry, and a second time to get divorced. I was surprised that divorce didn’t appear to be taboo and seemed much more prevalent that I’d expected. Perhaps his family was unusual, but there were two or three instances of it in the recent past. Of course the big difference in family attitudes was the custom of polygamy. It remained quite common, though most men seemed to restrict themselves to a couple of wives rather than the four that Islam traditionally permits. I never got a female opinion on this, but from what I could make out these arrangements operated with varying degrees of harmony. Mr Fall assured me that were a man to take multiple wives he would go to great pains to ensure they were treated equally. If he were wealthy enough this would mean establishing two households, and dividing his days two-at-a-time between them. If he wasn’t able to afford this, the whole family would live together and each wife would be treated equally until it was time to retire to bed, at which point he would again observe a strict rotation policy.

Mr Fall with one of the first year (6eme) classes

On a few times his jaw dropped at my description of life in the UK. He was bewildered at the revelation that friends of mine lived together before getting married. Though he didn’t say it, he was clearly thought such behaviour was the preserve of those too morally corrupt to be my friends. He was even more surprised when I assured him I don’t donate half my salary to my parents, perhaps thinking I was condemning them to grow old in penury. He told me how much he earned. Although it really wasn’t much he still dutifully handed half to his elders, “of course, of course”, flabbergasted at the suggestion anyone would do otherwise. However, the revelation that elicited the biggest surprise from him didn’t concern the family or money. In England, I told him, we don’t always take sugar in our tea. With even the “bitter” opening glass of the Senegalese tea ceremony containing a generous helping of sugar he simply refused to believe this. Every time he served me tea he checked this fact with me again, presumably waiting for me to eventually admit I was winding him up, and to this day I’m not sure he accepted my assurances. Towards the end of my stay he said that he’d had other volunteer teachers but I was the only one he’d spent time with outside of the classroom, and I regret that I’d not been able to find time to take up the invitation to visit his family. We joked about how I’d take up the invitation “next time”, but I hope that one day I will be able to follow this through. | ||

|